Grateful Dead: Eponymous Debut Album

The Grateful Dead’s debut album marks the emergence of a musical and cultural phenomenon, of which this recording is merely a small lens into what would become the greater whole. The eponymous record Grateful Dead is certainly somewhat reflective of their sound at the time, but as with most of their studio work, it is not completely representative of the band, nor does it provide but a mere glimpse of the whole. Each album in the Dead’s chronology can show the evolution of individual musicians, as well as the development of a musical collective, and an entity finding itself, becoming itself. Popular opinion would no doubt proclaim that the studio work barely reflects who the Dead were, and the only concession would be that only shadows or mere reflections are to be gleaned from the studio output. It is difficult to articulate and fully define the substance of what the Grateful Dead is, and if the recorded commercial albums were all that form the legacy, the message would be oddly superficial and incomplete. One striking aspect of the Grateful Dead’s work is their unconventionality, in nearly everything undertaken. What has become convention for popular music in the 20th century is so contrary to what the Grateful Dead did, and their success was born of that refusal, or more disinterest in following the path. The norm has been basically built around album sales and tours to promote the albums, or perhaps the other way around, or the synergy between the album and tour. The result is a concert that is the same in every city across the globe. The idea that the Grateful Dead would perform like that is preposterous, and if that had been their path, their success may have been marginal at best, and equally as ridiculous. The fact is that the Grateful Dead exist as a musical phenomenon in the sense that they are a thing to behold, right in the moment of their performances: a live act. The gathering of people to hear them became a cultural phenomenon in that an entire sub-culture sprang forth from the music and the spirit of the times from whence they came. The idea that a glance through their commercially recorded work would provide a decent platform upon which to gain a complete view of this spectacle is not circumspect. Despite this, the commercial recordings help to illustrate the mark left by the Grateful Dead in American culture.

The band has produced eighteen gold records, six platinum and four multi-platinum. The sheer output, combined with the industry honors for record sales, places the Grateful Dead in an elite league with some of the most influential musicians in history. Johnny Cash, Queen, The Who and Pink Floyd all equal the Grateful Dead in the number of gold records produced, while Frank Sinatra, for example, equals the Dead in multi-platinum albums. As a measure of success, it stands up. But album sales don’t really speak to but a fraction of their success, and really it might cause contemplation on the real definition of success. In hearts touched. Lives changed. Spirits moved.

The recorded legacy of this band is unsurpassed because they are one of the longest touring acts in the history of rock ‘n roll, and most of their performances have been preserved in quality recordings. That is why a complete account of the recorded legacy of the Dead is way beyond the scope of any analysis. But the commercial releases, however, actually provide a wonderful framework for the tale of the Grateful Dead phenomenon, and can illuminate why this musical ensemble has earned a place in the canon of American music, as have their cultural influences garnered an equally impressive place in history.

grateful dead: the motif of a cycle of folk tales which begins with the hero’s coming upon a group of people ill-treating or refusing to bury the corpse of a man who had died without paying his debts. He gives his last penny, either to pay the man’s debts or to give him a decent burial. Within a few hours he meets with a traveling companion who aids him in some impossible task. The story ends with the companion disclosing himself as the man whose corpse the other had befriended.

The name as synchronicity was thrust upon the group after their original title, the Warlocks, was suspected by bassist Phil Lesh to be the name of an existing group. After reviewing all sorts of other possibilities, the fledgling band opened a dictionary at random and the entry for the grateful dead rather appeared. The idea of this in literary terms is the notion that the world of the living and the world of the dead are more connected that perhaps we assume—that the duty of the living to the dead, to complete a circle, to bring completion to the toils of those previously living—provides the living with a sense of purpose that one might not otherwise discern. It also injects a sense of deeper meaning to life, and a study of the Grateful Dead itself can’t really ignore the idea that the journey of the band in its thirty-plus year career was one imbued with deeper significance, with the quest for meaning, for the spiritual quest, for the seekers of answers, for those who are more concerned with what is below the surface, with the deeper meaning of life and death.

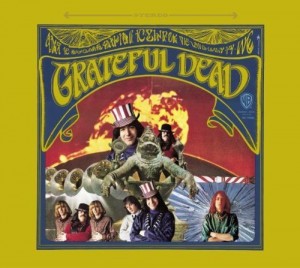

What better way to introduce the entire phenomenon than the self-titled album. Grateful Dead introduces the name of the band and its cast of characters in a fashion that begs inquiry. Stanley Mouse, a local graphic artist, designed the cover, featuring the band members in a collage using the image of a Godzilla-like Buddha sitting in front of the sun. If anything, they are not featured so much as placed in the scene. Granted, in comparison to their entire library of album cover art, this one was not as enigmatic as most, but the idea of hidden messages or simple visual puzzles will become a theme for the Dead’s album cover art. Along the top of the original version, the mythology of the band and its name is played up. “In the land of the dark, the ship of the sun is driven by…” And then the title: Grateful Dead. When this first image of the assembled album was presented to the band, they felt the message along the top was too bold, and they asked Mouse to revise. His re-worked version simply makes the message indiscernible, which in some ways exemplifies the fact that subtlety would become a virtue in both the music and the visual representations of Grateful Dead symbology. Modesty, humility, and subtlety would all become virtues of this group.

If we follow the imagery, we are invited to believe. This group, this music, brings light.

The music selected from the Dead’s repertoire, which at this point was fifty-six songs consisting of mostly covers, gives a good general snapshot of the band and their musical direction and interest, and on one level does reflect the sound of the band at this time.

Psychedelic music is a rather nebulous term, and I am not sure there really is an accurate consensus of what it really is. I think it is mainly satirized and yet in some respects that itself became an idiom. There are certainly currents of that sort of thing moving in this album. As the Grateful Dead would develop and advance in their career, they would become the definition of “psychedelic,” with no equal, but by this time they were far away in tone and ambience from what would ultimately be born. This stereotype of the genre is strange in a way, because psychedelic music depends to some extent on the listener’s experience of the music, and without the experience of psychedelics, one can only imagine what the experience is. If a listener is on psychotropic drugs, a rendition of “Row, Row, Row Your Boat” on a kazoo can have a psychedelic effect—“Hey, man, life IS but a dream.”

It is hard to say that this album is carved from the cloth of whatever is the perceived stereotype of psychedelic music, for a few reasons. One is basically that the Dead were one of the only musical acts to be so influenced by LSD in their own lives and as a musical act, and on some level the value of bona fide psychedelic experiences is not a casual matter. As the Dead played for the thirty-plus years they did, the depth of the psychedelic trip continued to develop and define itself. Another factor in this less than truth in recording was their producer, David Hassinger, who was more or less influenced by what he perceived to be the penultimate psychedelic sound, having produced the Electric Prunes, arguably an embodiment of the ersatz psychedelic sound. This was a point of ridicule possibly as the relationship with Hassinger deteriorated during his short working relationship with the band.

Whatever the case, and with any album, Grateful Dead is what remains as the document of the Dead at this time and is really a by-product of all the filters through which those that worked on the album viewed the work.

Still, it is important to articulate the irony of both the Grateful Dead as a commercial music phenomenon, as a studio session or recording phenomenon. The irony of the Dead recording with Warner Brothers is an interesting idea. Culturally, or in historical perspective, the movement of generational rebellion was happening as an event of massive proportion. The sentiment in this burgeoning musical family was an impetus to want to move away from activism vis-à-vis the Berkeley radicals and other political protest movements gaining momentum in the country at the time. Rather than taking up the cause of rebellion or conforming, young hippies were more compelled to simply step aside and turn from the direction of protest and activism—to simply go away from the tide of all of that to find the path without resistance or deliberation. If music labels and profit motivated music executives were an outcropping of the established paradigm, which this generation was evaluating often with the conclusion that they were not interested in playing along with corporate culture, it is ironic that they would play the game at all. In the same token, it is humorous that the record companies would approach this scene with the intention to capitalize on it. It is difficult to truly convey the sentiment. It was a collision of values, a generation trying to define itself and navigate the expectations before them. LSD was without equivocation the catalyst for the philosophy embraced or even incepted by the Grateful Dead. One thing that seems to have receded into the American consciousness is the fact that people taking LSD were doing so to explore a reality that was hidden, that only lived under the surface, and this chemical offered a means to smash the reality that socially, generationally, politically, this young generation was simply not interested in propagating. Its was the key to what they knew to be a deeper, far more significant reality. To see God was the invitation. Once you do so, the idyllic American life of suburban homes and a corporate job seemed trivial beyond measure.

Warner Brothers came to the San Francisco music scene in search of a way to capitalize on the erupting scene. They were out of their element and perhaps had no idea how to approach or work with the talent. The assumption was that their rules and systems were the accepted method, and talent came to play on their terms. This is a problem with the record industry long exulted or lamented—that the talent is a commodity rather than anything to respect, which is nonsensical in that the profit is driven by a product that is created by the talent, and the record industry has a long inglorious history of exploitation of talent. The Grateful Dead were aware that they wanted to and needed to record, but they were certainly aware of the disparity between artists and music executives, and they wanted to do what they were doing—playing music and having fun doing it. That they were able to negotiate such contractual concessions as they did is testament to the band’s initiative and desire to own their own artistic property, as well as WB’s desire to get a piece of the Haight-Ashbury trip. The deal they did put together with Warner Brothers was pioneering for the time, and potentially paved the way for artists to come. They retained publishing rights and ownership of their material, which was unheard of, and they also successfully negotiated an increase in royalties from 6 % to 15%.

The Grateful Dead entered with cautiousness in signing a recording deal, for their ideals were not really centered in rebellion or rejection of any system, but they were merely engaged in the idea of simply having fun with the experiences they were having with mind expansion and the making of music. The use of LSD, while opening these doors, also began to become fun. Fun became part of the band’s fabric. It is more in the spirit of this fun that the Dead approached their careers, ultimately.

The musical roots of the Grateful Dead very much speak to a sense of history, to a reverence for the American experience, to the depth and emotion of heart that the American songbook offers. Folk, blues, bluegrass and traditionals draw from the American experience, and this is where the Dead were born. I think it is a sense of history that propels a quest for meaning, for the messages and lessons that are repeated through history, with symbols and images that begin to retain a collective import. This approach to the human experience through the ages is such a spirit in the musical direction of the Grateful Dead. T.S. Eliot spoke of an artist’s sense of history, and their homage to it, coupled with their own sense of the contemporary that makes a good artist. He said, “the historical sense involves a perception, not only of the pastness of the past, but of its presence.” The music the Dead would select to cover, as well as to write, would reflect a sense of that history and their own place in the contemporary world.

Music really speaks to the heart of the listener, allowing a connection to form between the performer and the audience—creating the memory of emotion and perhaps allowing us to experience such emotions with the additional security of knowing they are shared, and to experience them again and again in song perhaps gives us a sense of wisdom and belonging—belonging to a continuum of emotional experiences, and perhaps instilling a feeling of not being isolated and alone in the emotional world in which we might feel alienated. Good music, that is.

What ended up a mega-touring act in the rock music scene began as a jug band, nee Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions, playing gigs in small cafés around the Palo Alto scene. The material was drawn from folk and blues standards. Later, they would become the house band at the Prankster acid tests, then a part of the burgeoning San Francisco music scene, but it began with a collective quest to play music, and an interest in musical tradition.

Click here to continue to the next installment, “The Golden Road (To Unlimited Devotion)”

One Reply to “Grateful Dead: Eponymous Debut Album”

Amazing history!